|

|

|

Edited by Orpha E. (Peggy) Galloway

Copyright 2000

Pages 84 - 87

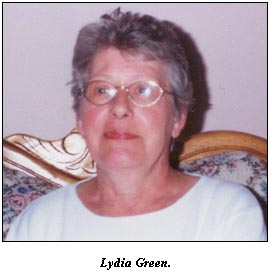

LYDIA GREEN

In 1939 when the war broke out the Russians asked us to get out of the country. My family and all the other families moved to Poland just outside Warsaw. Our years there were pleasant; we never knew there was a war going on.

We were of German descent. We were German citizens yet living in foreign land. Being German, we listened to the German radio and were told if we wanted to get away from the war to move to Germany. Everything was packed into wagons and we left. Unfortunately we didn't make it very far. We got closer to the German border and of course the front had been moved towards Poland. They were invading and we were captured. We had to march back where we had come from. We were thrown into a cell and everything that we owned had been taken. Valuables were stolen from us; clothing was taken, and burned, and we were sent back to Poland.

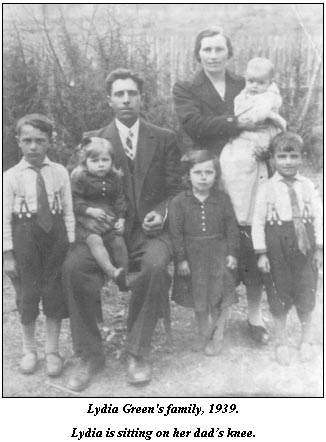

In 1943 my father received notice that he was drafted to the German Army. He left in early 1944. We thought everything was fine and that Dad had just gone off to war. A few months after my dad left we found out that this was serious stuff.

In 1944 I was seven years old. I can't remember how far we made it towards the west but it was pretty close to 200 kilometers towards the German border. There was my mother and at that time I had four brothers and two sisters. We were left destitute; everything was taken and we had to walk the 200-kilometer trek back to Poland in the dead of winter. We had no proper clothing and we walked every day. Food was unheard of. If you could beg or steal something, that's what you did just to survive and that's how we lived. My mother had seven children and the youngest one was eight months old and the next one up was three years older so therefore she carried one on her back and one in her arms through the snow, but we made it back. Fortunately we didn't lose anybody. We saw a lot of people dying either from exhaustion, hunger or the bombs because by this time the bombs were flying everywhere. When there was a raid or an aircraft going over you just made for the woods.

When we first got back we were put in a camp and every night there were beatings; not so much the children, it was more the adults. I had one aunt who had all her teeth knocked out. My uncle who couldn't go into the Army because of illness was beaten terribly. Somehow through the grace of God we made it.

My mother was an exceptional woman. She tried to keep us around her at all times but it didn't always turn out that way. We went into a camp, complete with barbed fence. Luckily we didn't have to spend too much time there but when they let us out it was no better than being directly in camp because we still had no clothes, no food, no accommodations. We were in a Russian concentration camp. We didn't know that there was such a thing as a concentration camp, and we also didn't know that the Jews were being led away. We knew Jews were leaving because even where we lived there were quite a few Jews that left but we were basically told that they left on their own free will. For two years we thought that the Poles had nothing to do with the disappearance of the Jews or that the Germans had nothing to do with it. We were told that the Jews left for greener pastures and that they didn't want anything to do with the war. It was not until after the war that we found out what had happened to the Jews.

Unfortunately East Germans did not realize the deviousness of Hitler. Hitler started out doing everything right for the German people. Then he switched in midstream and used the German people. The citizens of Germany were as badly abused by Hitler as all the other nationalities. They were not told what his motives were, that he had big plans of ruling the Universe. We knew less than the Western countries knew. Most of the Europeans were uneducated people who couldn't read or write and therefore couldn't really know what was going on.

There was no food in the camp for us. We used to go through the garbage cans and pick up a piece of stale bread or potatoes or whatever was in the garbage, and we ate it. It was a matter of survival. Our mother did go and work and she would come home with a few crusts of bread. She worked in the kitchen and did laundry. While she was away the older children would look after the baby. We all learned our responsibilities early. They did allow Mother to come home during the day to nurse the baby. Mother nursed the baby for two years. It was the only way she kept her baby alive. When you see starving children with bloated bellies that's how my sister looked. Her arms and legs were like little sticks.

When you are starving you will eat just about anything and you are constantly in pain. You can't think clearly, and all you are thinking about is food. You do get to a point where you don't really envision anything in the future; it's just survival right now. The camp was like a barrack and we slept on the floor. There were no beds or blankets and we used logs as pillows. We always looked forward to our mother coming home at the end of the day; it was all that we had to look forward to. I can't condemn every soldier. Some of them would sneak us a slice of bread. I believe there's good in everybody.

It may seem hard to believe but my sister and I shared the same pair of shoes and that's difficult to do. She had her shoes taken from her. I had hidden mine so we ended up sharing.

Our mother had much to deal with being the sole provider for her children. She had great love for her seven children and would have given her life. The hardships she endured eventually took its toll and she died at the age of 42.

During this time we saw our father only once during a short furlough and then we never saw or heard from him again until 1946. He was one of the luckier ones. He became sick two weeks after he was sent to the front. He was put in the hospital and that's where he spent the rest of the war. He never saw any action. Basically, you could say he had the "Life of Riley".

We didn't know the war had ended until the spring of 1946. In April of 1946 we moved into a one-room apartment in Northern Germany. "We were deloused and put back into humanity". We arrived in a horse-drawn wagon with the entire town to meet this new family of seven children with heads all shaven and ragged. As children will be children, they made fun of us and it was very, very hard. We had been stripped of everything; our pride and our dignity, so we had nothing left. We never made any lasting friends because we were known as the poor people. Our father had been trying to find us and eventually with the help of the Red Cross we were united as a family.

Our father had been away from home for so long that he now appeared like an intruder. We didn't remember him and now we had this man who came between Mom and us. He demanded some time with Mom. The time that she had devoted to us now had to be shared with a man. We didn't accept him that freely. My dad never was a big talker. He was a very quiet and reserved man. It was difficult to communicate with him so we shied away. Dad would come in the door and all of us would just clam up. After his many years in the hospital Dad looked normal whereas we didn't, so we kind of resented him. Children in a sense are very resilient and yet they also don't like changes. It wasn't until our mother passed away that we became close to Dad.

In 1950 our mother passed away; she went to bed one night and never woke up in the morning. We never knew what she died from because we had no money for an autopsy. Her burial was very primitive in a sense because Dad made the coffin. Some of my aunts had come for the funeral, and we kept the body in the barn until the day of the burial. Dad said that before Mom died they had talked about sending the healthy kids to Canada.

We soon realized we had no future in Germany. My dad was illiterate and he couldn't get a job in the city. He was a farmer and we had no money to buy a farm. As a farm hand you just didn't make enough money to support a family. Mom and Dad had relatives in Canada. They had tried to get us to immigrate in 1949 but because of my dad's health we were refused. My younger sister and my older sister at the time were also not well. Dad decided that he was going to send five of us to Canada. This meant two older brothers, two younger brothers and myself. On October 1, 1951 he put us on the ship Beaverbrae to head for Canada, a journey that took nine days. None of us spoke English; we each had one change of clothes and this was how we headed for Winnipeg.

We arrived in Quebec City and were positive we had reached the land of milk and honey. The docks were so spotless and there were flowers everywhere. We boarded the train for Winnipeg on the 11th of October. Oh what a tiring train ride that was! The whole ship had been full of immigrants, a lot were displaced people. Because we had sponsors, because our relatives had paid our fare we were classed as immigrants. On the ship they had the women and children on one side and the men and older boys on the other side. I unfortunately was seasick the entire nine days. I lost so much weight that by the time we arrived in Quebec and I changed my outfit, the buttoned skirt fell right off me.

We arrived in Winnipeg and there was no one to meet us. We sat and waited until finally I heard someone mention our German name. I said, "That's us." It turned out to be my mother's sister. They had arrived to greet us but the station was so filled with people they had to wait outside until there was room to enter. We didn't know with whom we were going to live or what the arrangements were. I was told that two of my brothers, the oldest, the youngest and myself would be moving to Morris, Manitoba.

I had a very hard time adjusting to life in Morris, Manitoba. First of all, there was a language barrier. The family I lived with also had children my age, but they didn't speak German, and I didn't speak any English. On my first day of school I walked in and I was ready to walk out as everyone was staring at me. At the time I was just fourteen years old. The relatives in Morris were very religious people and it was to the point that everything you did was a sin. To play ball was a sin. Going to movies was a sin. Dancing was a sin. They went to church every day and because they were our guardians we had to do the same.

In the spring of 1952, we received word that the rest of the family was allowed immigration status. We knew they were coming; we just didn't know when. My uncle gave me a bit of garden and I planted a lot of cabbage, cucumbers, and potatoes. In the fall I started canning. I never did so many jars of pickles as I did then. I put up all the sauerkraut. With Dad and the family coming my brother said I couldn't return to school, so I lied about my age and managed to get work.

In January of 1953, Dad and the rest of the family arrived in Winnipeg. Now our family was united again, and I was very happy.

We had a lot of difficulty renting a house because no one wanted to rent a house to a single man with eight children. We ended up living in what you would call a slum area but we kept our noses clean. We worked hard. I earned $25.00 a week, $20.00 would go to Dad and I would keep $5.00 for myself. My brothers did the same. Dad worked as a carpenter's helper and other odd jobs. With all of us chipping in our money, we lived quite comfortably.

A year after Dad arrived in Canada he bought a house. Because Dad had to have a mortgage he rented out the second and the third floors. We all squeezed into the main floor and believe me we used every inch of space. We paid the mortgage month after month, and we had lots to eat. Nobody was lacking anything and because we didn't know any better, we never needed a lot of money.

Dad didn't speak English when he arrived but he could speak six other languages. He was fluent in Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, German, and Yiddish. When we tried to get Dad to speak English at home he said, "I don't need English. I can go anywhere I want in Winnipeg and find someone to talk to."

I learned to speak English by attending a lot of movies but one of my first purchases here in Canada was a Webster five-pound Dictionary and that went everywhere with me and I still have about half of it. If I wasn't at the movies I was at a dance. I just loved to dance. Movies and dances are what I enjoyed doing. I never had any intentions of getting married because I was enjoying life.

I met my husband at one of these dances and after a year of courtship we were married in 1958. We were blessed with one son and two daughters. Our marriage of over forty years has been wonderful.

I live life one day at a time and accept what comes my way. You can't give up!

This story was written by Bernice Welden from a video taped interview with Lydia Green.

Editor's Note:

Lydia Green's story was the catalyst confirming my opinion that a book of women's personal stories of the war years was long overdue. Many people compelled to endure the horrible conditions Lydia and her family experienced might have become very bitter. Not so with this lady. Her personality has the same warmth and compassion as her countenance.

I was privileged to interview her and her husband Ted for Access Television. We thank you for sharing your memories with us Lydia, and wish you both well.

|  |